If you follow our blog series, you’ll be aware of our Simsek Turkish style bow, which performed well but broke. This should not be judged too harshly, anything which exists so close to the edge will have a failure rate, and all good bows exist close to this limit as a result. What if a bow doesn’t exist close to this limit, wouldn’t that be better? No actually, it would not, because it would mean it has latent performance, it could have been better; performance is maximized by sitting close to that edge. I digress. The Simsek Turkish style bow pulled up a splinter on its belly, a compression failure, which progressively grew larger and it was clear would continue until the limb catastrophically failed. A shame, because it was a beautiful bow.

Simsek though handled the situation, and said they’d replace it. Given the comments in our review regarding the merits of a Tatar style bow, Simsek asked if we’d like their new not-yet-released Tatar style bow? A few months later and we had one of the new Cagan bows in hand.

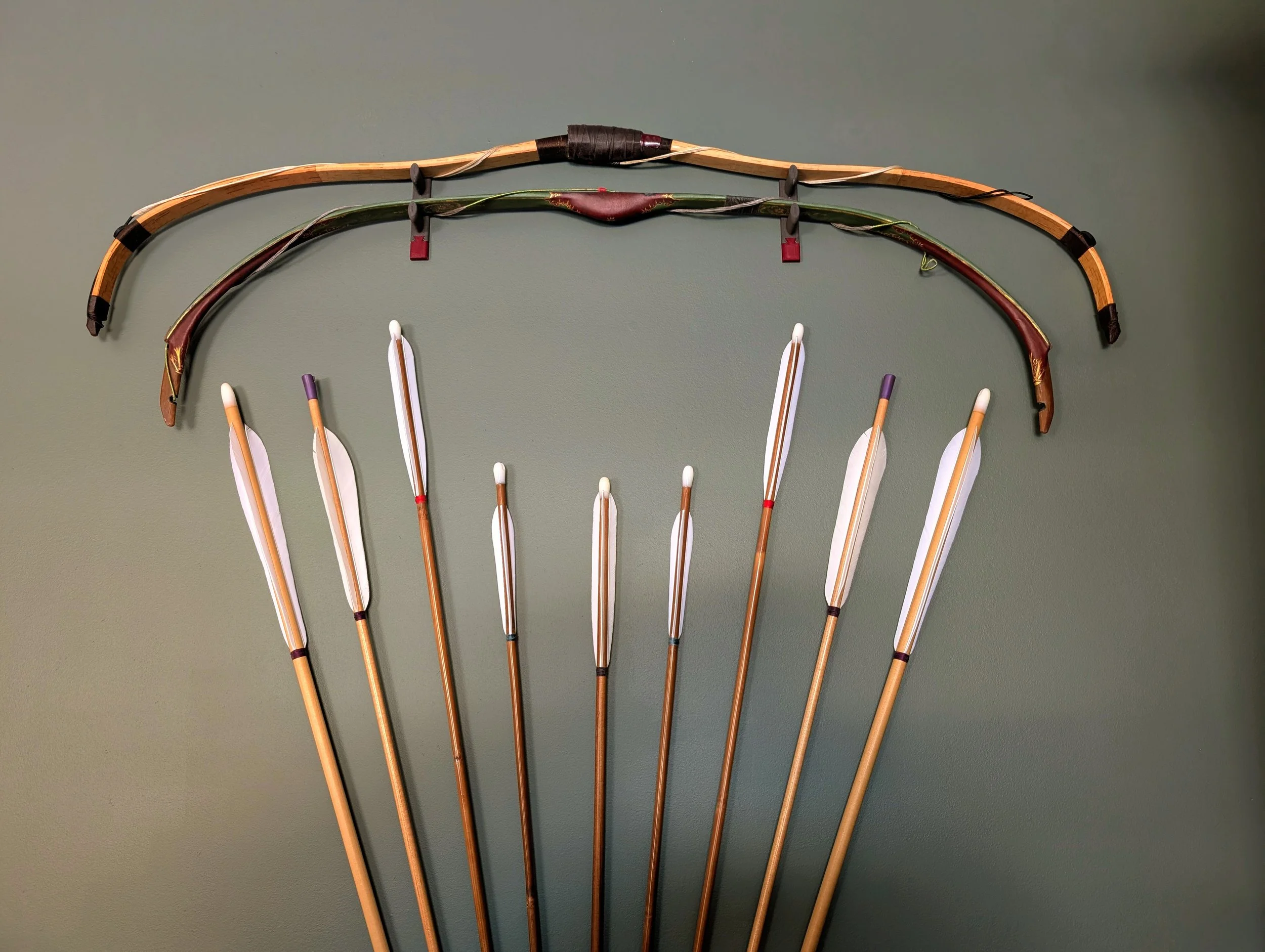

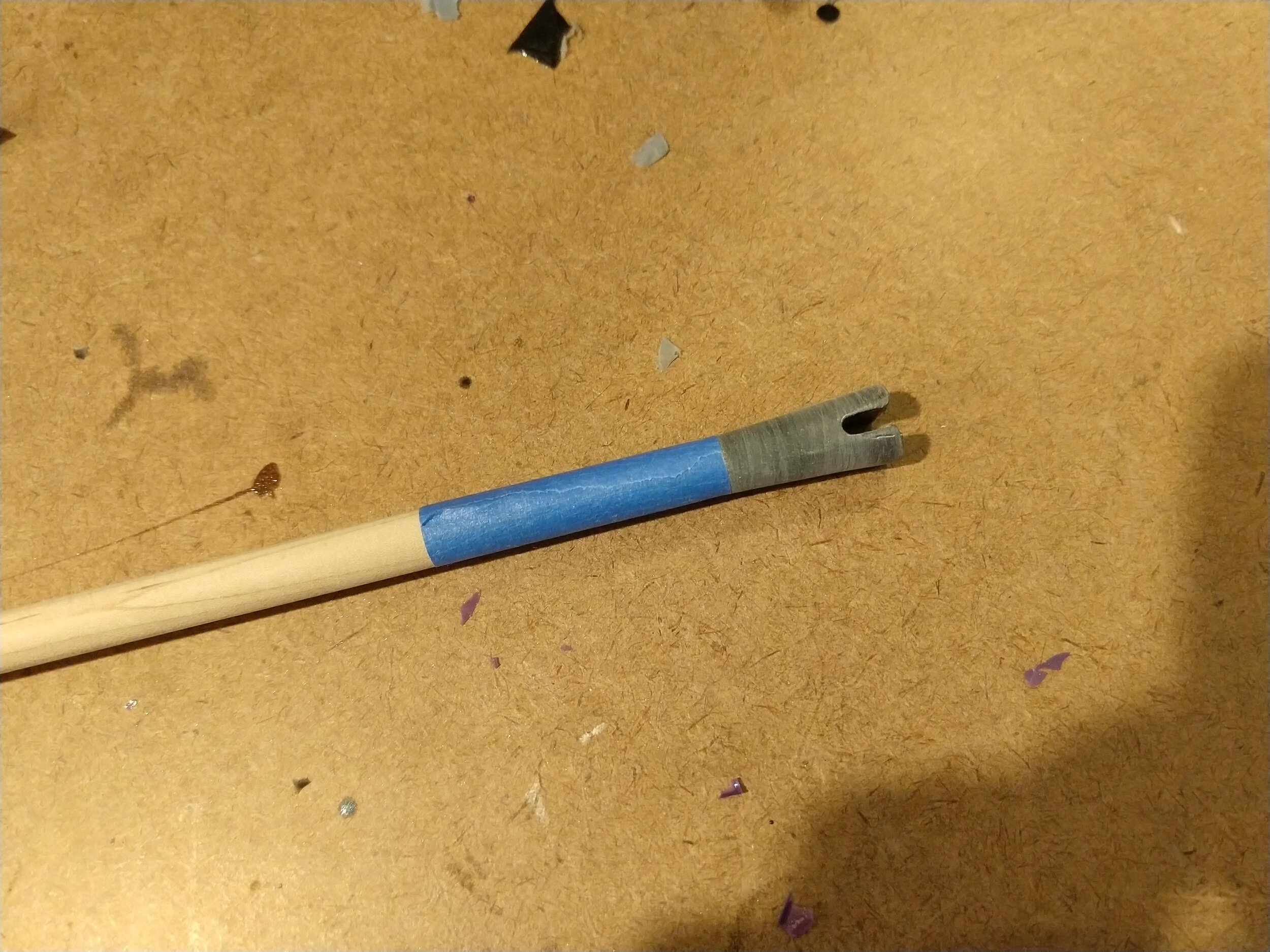

First impressions are that the bow is still very much Simsek. Limbs are very narrow as are siyahs and grip. The bow, again, feels very slight and delicate in the hand. And both unstrung, strung, and at full draw it possesses absolutely sinuous curves. It is a very shapely attractive bow. This bow though, instead of having its back covered with leather and painting and its resin and glass belly exposed with voids visible, is almost entirely covered in what Simsek confirms is some sort of synthetic material. It looks rather like black painted cork. As it abrades away at the arrow pass, it reveals some sort of woven underlying structure, perhaps a cloth integral to the wrap? If I were to guess, I’d guess it is some sort of patterned vinyl wrap. Only the Siyahs are exposed, which have a better quality of finishing than the previous bow. New style larger nock inserts and more rounded string bridges are welcome improvements as well, reducing string fraying.

Upon first drawing this bow, there were some truly heart-stopping popping sounds. I’m not sure of their origin, and these sounds have diminished significantly as the bow has been shot, although they still occasionally occur. It is possible they are, not the fibers of the bow structure, but the fibers used in the covering. This is just a guess of course, but I have two reasons for suspecting this is the case. The first drawing was quite dramatic, with many popping sounds, and that was never repeated. First, surely these bows must be drawn for tillering and testing before shipping, and if it were the working part of the bow that would have already been gotten-over-with. However it is possible Simsek covers the bow as a final step, thus the covering hasn’t been fully stretched and would produce these sounds. My second reason for thinking this is that the original Turkish, which I believe has the same functional composition, didn’t do this. Third and finally the bow hasn’t shown any physical signs of failure or degradation, so it seems unlikely they originate from the working part of the bow. We will of course update the blog if any of this changes.

Shots from this bow, again like the Turkish, have an effortless quality to them. While the grip really increases the perception of force in the hand in all respects, arrows glide out with seemingly effortless accuracy. It is pleasant bow to shoot, requiring little effort or input to deliver arrows right to the target. They don’t seem to have any great sense of urgency though, and at range seem to always land low.

All this is brings me to really the first significant complaint about the Cagan: its maximum draw length. The previous Turkish bow indicated an optimal draw length of 28-30” with a maximum of 32”. The Cagan cuts off those last two extra inches, capping it at a mere 30.” And that really puts a pin in the style. Let me offer a somewhat simplified explanation.

The philosophy behind the Turkish style of bow was an optimization for arrow velocity, with some sacrifice in absolute efficiency and power. This evolved into a bow which was unusually short and fired arrows on the short-side of things. The Ottoman military used Tatar soldiers though, and so there was demand from Turkish bowyers for their style of bow as well. The Tatar bow was still a fast bow in the global scheme of things, but used longer heavier arrows and a greater focus on ultimate efficiency and kinetic energy delivery to the target than its Turkish counterpart. In that regard, it was more akin to the Korean military style of bow, and I think it no accident the two ended up rather similar in profile and size.

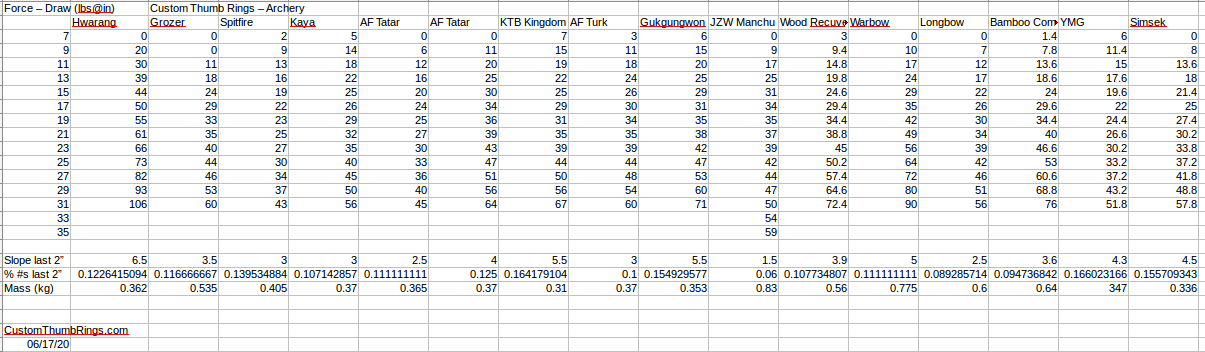

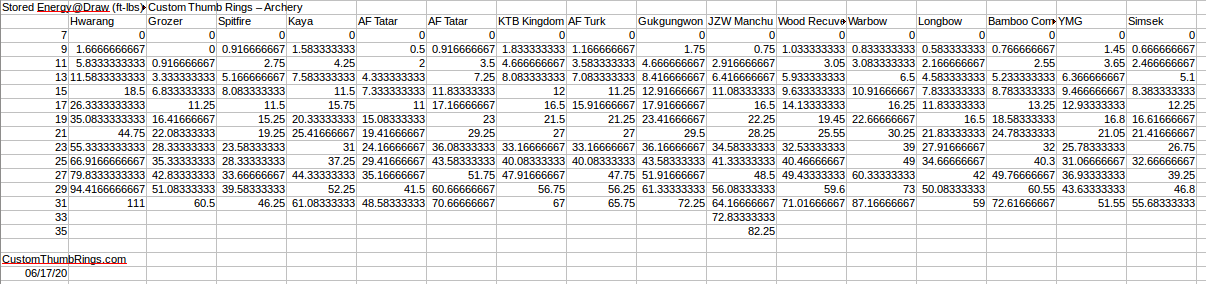

Why does that matter here? Well the Simsek Cagan has a shorter maximum draw than the Turkish bow it is replacing. And that lack of power stroke really hinders it. If we assume draw force were even (it isn’t), the specified brace height of the Cagan is about 6.7 inches (17cm), so you get a power stroke of about 23” and that is about 10% less than the Turkish. And even if you were to assume equal draw length, the bow is 2.4” longer and 7% heavier, at 362 grams. Once again little space or mass is wasted in the grip, so these don’t bode well for the bow’s performance. So one would have to ask, other than for style, why would you want the Cagan compared to its Turkish cousin? We did put this question to Simsek before publishing and their response was “…no bow design is better tnan the other. All have their advantages and disadvantages...” [sic]